| COST | INSTITUTIONAL SEGREGATION | TRACE |

Lumber Yard Pavilion

| Revealing Site Traumas |

RISD, Fall 2022

The device produces a curve that extends from the user’s spine, comparing the user’s posture as it confines within the site conditions. Regardless of how the body contorts, the device will always meet a limitation where the body’s curve ends and the conforming curve begins. Throughout this presentation, we will find an understanding of the pavilion through the actions of our bodies, and how that choreography determines the moral value of the pavilion.

We begin with my device: an extension of posture in confinement.

In 1955, there was no park. What existed was a lumber yard and docking ports— a small peninsula. Beyond the lumber yard existed the thriving Jewelry District. Between 1949 and 1960, the Providence Redevelopment Agency displaced over 14,000 people out of their homes, primarily targeting and demolishing the redlined section of African American residents. This is all in the name of “urban renewal,” said to be necessary for the city’s growth towards auto-centrism and extorting the land to attract capital. Today, beneath our feet and beneath the pavement lies the footprints of segregated land— this is the cost of our freeways, and this is the cost of the Innovation District Park.

This is the Innovation District Park, in 1955 and today.

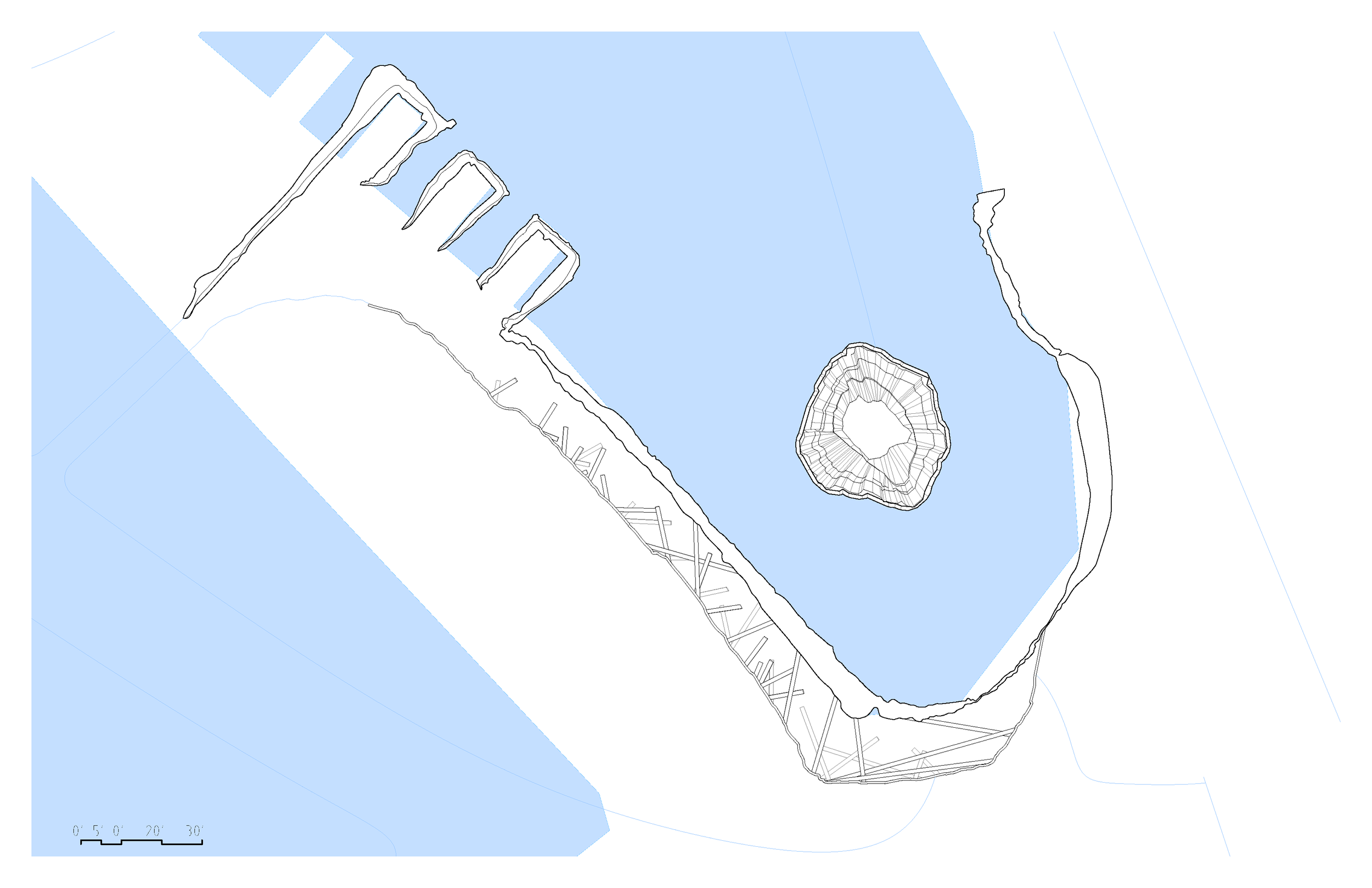

This is the Lumber Yard Pavilion, an eruption of the peninsula and ports out of the ground to reveal the truth of the land. There are political implications in the act of placing a pavilion in a public park in a central city— especially upon land that’s been segregated, displaced, and silenced with continuous developments. A public pavilion draws capital and expensive beauty to the site at the interest of an exclusive, privileged population, whose intentions draw similar parallels with “urban renewal.” In recognition of this, the Lumber Yard Pavilion remains as a lumber yard, and invites users to navigate the pains and obstacles that the land and history had to endure.

This is the Lumber Yard Pavilion, an eruption of the peninsula and ports out of the ground to reveal the truth of the land. There are political implications in the act of placing a pavilion in a public park in a central city— especially upon land that’s been segregated, displaced, and silenced with continuous developments. A public pavilion draws capital and expensive beauty to the site at the interest of an exclusive, privileged population, whose intentions draw similar parallels with “urban renewal.” In recognition of this, the Lumber Yard Pavilion remains as a lumber yard, and invites users to navigate the pains and obstacles that the land and history had to endure.

We then navigate down the ramp and encounter obstacles of lumber wreckage, ejecting out of the land.

As we duck, dodge, and climb, our bodies are forced to move and make way to the lumber— just like how urban renewal forced the Jewelry District residents to move, dodge, and climb out of displacement.